Oral history is the spoken word in print. Oral histories are personal

Oral history is the spoken word in print. Oral histories are personal

memories shared from the perspective of the narrator. By

means of recorded interviews, oral histories collect spoken memories

and personal commentaries of historical

significance. These interviews are transcribed

verbatim and minimally edited for readability.

The greatest appreciation is gained when one

can read an oral history aloud.

—Kate Cavett, oral historian,

HAND in HAND Productions

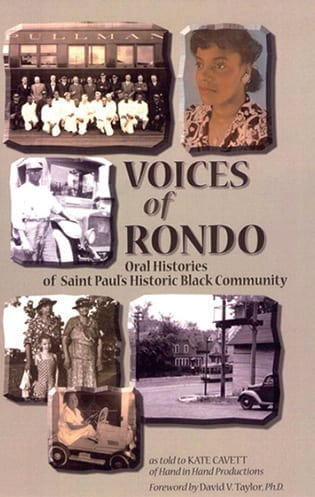

The following oral history is excerpted from

Voices of Rondo: Oral Histories of Saint Paul’s

Historic Black Community and is used by permission.

Voices of Rondo won a 2006 Minnesota

Book Award.

Courtesy Kate Cavett

My name is Debbie Gilbreath Montgomery.

I grew up at 978 Saint Anthony, which

is on the corner of Saint Anthony and

Chatsworth. I was adopted by my grandparents,

Isabella Gertrude Gilbreath,

whom I called Mama, and Elbert Gilbreath,

whom I called Dad.

Back then our neighborhood was a village.

If you did something wrong or said

something out of line or didn’t respect your

elders, you were going to be disciplined.

You probably got lickings before you got

home, and then when you got home you got another one. So it was

a strong village environment, and everybody looked out for each

other’s family. If you needed something, you could holler across the

street. If you needed a couple of eggs, or some milk, everybody kind

of shared, Whites and Blacks together. It was a really close-knit

community. It was a really loving community. People cared about

you. They were concerned about your success.

Oxford Playground was a block away from our house. Back then

it was a swamp. Bill Peterson was a twenty-one-year-old Marine

who had just got out of the service. And he’s got this playground

that was a swamp. All it had on it was a little old warming house

along with a merry-go-round and six swings. Here he’s got all these

little Black kids and a few White kids and he’s sitting down there

trying to teach us how to play ball. We learned how to play T-ball

and softball and baseball.

I was a jock. I was very athletic and had a lot of energy. I was a

little wiry thing. Down at Oxford, you had Dave Winfield and Paul

Molitor. Bill Peterson was the baseball coach of the boys’ Attucks

Brooks–Legion All-State baseball team. Paul Molitor and Dave

Winfield and all those guys, they all played on those teams, and

they all came through Oxford.

Because it was a swamp and the field was not real good, nobody

would come out and scrimmage our girls’ team. A lot of the other

rec centers wouldn’t come and play us in our park because we

didn’t have a good field, so all of our games were away and a lot of

our parents didn’t have cars. The girls’ softball team would scrimmage

the boys’ Attucks Brooks baseball team. Dave Winfield was

the pitcher then and Paul was shortstop. We’d all be playing ball,

and these guys were throwing that ball in there like they were

throwing to guys! Anyway, I ended up being one heck of a softball

player. I’d hit the ball Dave was pitching, and I’d just cream it! To

this day, David’ll say, “Boy, she just killed my pitches!” I was a good

softball and basketball player and I ran track. I was a speed skater.

In the wintertime, Bill would get out there and flood this area

for us to skate on. He just kept us engaged. Then he’d go out and

beg, borrow, and steal skates so we all could skate. I must have had

the biggest feet, because I ended up getting black speed skates. The

other girls had white figure skates and the boys had hockey skates.

For the Winter Carnival, they would always have the races out

at Como Park, and so he’d put all of us in his little red 1954 station

wagon and drag us out to Como. We’d get out there, and I didn’t

know how to speed skate when I first started, so I literally outran

people around the ice on these speed skates. Finally, they took an

interest in me and saw that I had potential, and Bill got a couple

of guys to work with me, to try to teach me how to stride and how

to skate. I became really, really good. I got all kinds of blue ribbon

medals from skating at the Winter Carnival. I beat Mary Meyers,

who tied for the 1968 silver medal, two out of three heats in the

tryouts.

They had two speed skating clubs that were close to us. The

Blue Line Speed Skating Club, which was kind of a high-buck private

speed skating club on this side of town, and East Side Shop

Pond, over on the East Side. Because the Blue Line Club was over

here, Bill took me over to try out for the club, but they weren’t letting

any Black kids in. The East Side Shop Pond would take me in

the club, but we didn’t have any transportation to get there. To this

day, Peterson says, “What could you have done if you had had any

kind of training?” I was obviously an athlete before my time.

There were so many things going on back then in the 1960s, that

skating wasn’t an important deal. The sports part was secondary

to people getting the right to vote. You know, we didn’t get the voting

rights bill in until 1965. We didn’t get open housing in Saint Paul

until 1960. So there were just tons of issues back then, and sports

was an outlet for me. It felt good to succeed, but I never dwelled

very much on “this is an opportunity missed.”

When I was maybe thirteen, Allie May Hampton was a good

friend of mine, and when I say friend, she was an older woman that

was real active in the NAACP. She was just a gem. She saw I was a

rabble-rouser and intelligent and articulate, and she got me active

in the NAACP. She was getting us involved in the political process,

getting us to understand the issues that were going on back then.

This was in the late ’50s, early ’60s. She took me to my first NAACP

conference. After I came back from the conference, they made me

the president of the youth group.

I got all the kids involved in the NAACP youth group. We had 650

kids in it back then, because we had tons of kids and there were

a lot of issues going on. I got really involved with the civil rights

movement after that first conference and meeting all the kids

from the South and the East and the West. Listening to what was

going on down South, none of that was going on here like it was in

the South. Our schools were integrated.

When the civil rights movement started they had buses going

down to Mississippi and Alabama. In Minnesota, we were good for

sending White activists down, and I was one of the Black youth

that went down there.

Mama was scared to death because she was from Starkville,

Kentucky, and Dad was from Lubbock, Texas, so they knew about

the South. I didn’t have a clue about what was going on, other than

I knew I was fighting for a cause, and not realizing that people were

killing people. I mean, I did realize it, but I didn’t think it could happen

to me.

I went on the bus with a lot of White kids and White adults and a

few civil rights folks, and we got down there and we demonstrated

and then got on a bus and came back. We were fighting for voting

rights. I was probably about fifteen then. My parents were just

scared to death, but I was just kind of a freewheeling kid. “I gotta

go do the right thing for the right reason.”

I became involved in the NAACP youth branch at the national

level. We had to go down to Chicago, Atlanta, or Baltimore for

conferences. Dad, he’d get me a pass and put me on the train. Dad

and Mama never rode the train in their whole life, but because

Dad worked with the railroad they could get passes. He’d take me

down to the depot. He’d hook me up with a porter, one of his porter

friends, and the porter would put me on the train. They’d usually

put me in the food car because they could feed me there and make

sure I was taken care of. Then when I got to Chicago and had to

transfer, they’d take me by the hand and take me to another train

and hand me over to another porter and say, “This is Gil’s daughter.

She’s on her way to Baltimore, and she’ll be comin’ back at suchand-

such a time. If you’re on the train back, tell ’er where to meet

you when you let ’er off. Let ’er know that you’ll pick ’er up when

she comes back.”

Courtesy Kate Cavett

When I was seventeen I was elected

to the National Board of Directors for

the NAACP. As I said, at fifteen and sixteen,

I had gotten really active in the

national youth movement, so I made

friends with the children of the national

NAACP leaders. I was just a rabblerouser.

We were all active in the national

youth movement, and so they’re telling

their dads, “Oh, man! She’s neat, man.

She’s smart. She’s articulate. She’s from

Minnesota.” They thought Minnesota was off the world. So the kids

got together at the national youth branch and said to me, “We’re

going to run you for the national board.” They got together and they

rallied all the kids together, and they got their parents together.

If you look at the NAACP history you’ll see that at the age of

seventeen, I ran nationally, at large. I got elected to the national

board of directors, with Roy Wilkins. I mean, all of the people that

you see in there, and here’s this little seventeen-year-old girl out of

Minnesota that’s sitting at the board with all these big shots.

I was on a mission. I was fighting for civil rights. I was speaking

up for people. Trying to get voting rights for the people. I mean,

these Black folks, they were in the army, they were serving their

country and yet they didn’t have the right to vote? If you look at

the history, Blacks were on the front lines and getting killed in

larger numbers, and they didn’t have the right to vote. They didn’t

have the right to own property. They had the poorest jobs.

On the national board it was interesting to listen to the discussions.

I mean, you had lawyers, bankers, politicians. You had lawyers

that were talking about legal issues. Thurgood Marshall, how

he was going to deal with the legal issues taken to the Supreme

Court. What’s going on in Missouri? What’s going on in Kansas?

They had huge issues, and you’re sitting there and you’re listening

to the discussion and listening to how they’re going to handle it,

who they were going to target. They were killing young people that

were going down there in cars, similar to what I was doing.

I was kind of blessed. I marched from Selma to Montgomery

with Dr. King, and I was in the March on Washington when he gave

that “I Have a Dream” speech. There were just so many major issues

going on back then, I didn’t have time to think about little things.

My mind was always out here. I’d come home and the adults here

were always talking about how bright I was. I wasn’t any brighter.

I was just kind of active in everything, trying to figure out how you

make things work.

I look at Mama and Dad and the folks on Rondo. They did not

get high-paying jobs, but never once did I feel that we were poor.

There was richness in our house. There was a strong faith in our

house. My faith has been the stronghold in my life. I don’t look at

the downside. I just saw the up, and I wanted to help the next generation

move up.