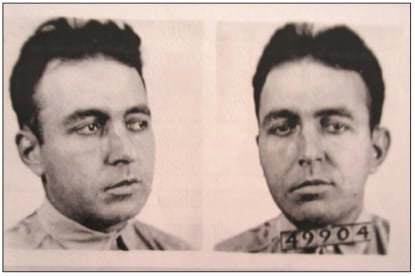

Photo Courtesy Rosemary Ruffenach

Among our family stories is one with a lesson: Don’t try swimming with the sharks. It was Matthew William Stegbauer Jr. who had to learn it the hard way—with hard time. Matthew, known as Mattie, was born in 1910 as the oldest son of Hungarian parents who had immigrated early in the twentieth century and settled in Saint Paul’s North End among other recent arrivals from Austria/Hungary and Bohemia.

At age six he was enrolled at nearby St. Bernard’s school, made his First Communion at thirteen, and was confirmed at fourteen. He played the trumpet and baseball while receiving grades averaging in the seventieth percentile. Upon matriculating to St. Paul Boys Vocational School, Mattie learned the printing trade. Up until his mid-twenties, he worked as a bartender and as a printer at Brown & Bigelow. In his off hours, he hung out at Matt Weber’s Saloon at 20 East Seventh Street. At Brown & Bigelow, he encountered the flamboyant vice president, Charlie A. Ward, who had worked his way up the company hierarchy after his release from Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

Ward, sent to Leavenworth in 1920 on a narcotics charge, had managed to secure special privileges, and in 1924 took Herbert Huse Bigelow, incarcerated for eight months for tax evasion, under his wing. Released in 1924, Ward claimed a job at B & B, where he made a meteoric rise through the ranks, assisted by cutthroat tactics and a cadre of ex-cons whom he had hired.

To place events in context, the William Hamm kidnapping took place in June 1933, followed in January 1934 by that of Edward Bremer. Between the kidnappings, Bigelow drowned with two companions in Minnesota’s Basswood Lake under mysterious circumstances. Only five weeks earlier, Bigelow had changed his will, leaving Ward about one million dollars and a controlling interest in B & B. No criminal investigation of the drownings was conducted.

In December 1935, crusading journalist Walter Liggett was gunned down in the alley behind his Minneapolis home. Liggett had fiercely campaigned against political corruption, naming Kid Cann, racketeer kingpin of the Minneapolis liquor syndicate; calling for Governor Floyd B. Olson’s impeachment; and publicizing Ward’s seamy background. The Chicago Tribune’s publisher called the Liggett assassination “an attempt to throw the entire state’s press under a reign of terror.”

When held in Stillwater Prison, Dillinger gang member Tommy Gannon wrote an undated confession that placed my ancesor Stegbauer in one of the two cars used in the Liggett drive-by shooting and named a Ward hire as one of the shooters. (Kid Cann was charged with the murder, but not convicted.)

Four months later, Stegbauer and three companions hijacked a liquor truck making a run down from Canada. They bound the two truckers and drove across state lines to get food in Grand Forks, making the hijacking a federal crime. His 1936 prison admission summary states that Stegbauer was “undoubtedly a vicious under-world character.”

Three months after his November 1938 release on probation, Stegbauer attempted to extort $15,000 from “Uncle Charlie” Ward to keep quiet about the latter’s involvement in the Liggett murder. The blackmail note, which displayed inside knowledge of the event, was turned over to a Saint Paul police buddy of Ward’s and “lost.” Under police questioning, Stegbauer and partner Harold McAvoy retracted their accusations. Oddly, it was a good two years later that Stegbauer was sent to Sandstone Federal Prison to complete the 252 days of his original sentence, since he had “violated his parole.” No charges were filed for the extortion attempt.

Following his release, Matt managed to keep out of trouble. Apparently, he had learned the shark lesson and its corollary: Don’t mess with “Uncle Charlie.”