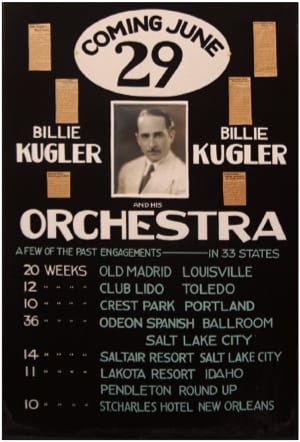

Photo courtesy of the Schubert Club

I spent two summers semi-underground in Saint Paul. I worked in a corner of a municipal building’s warehouse near the Mississippi River. It was, more accurately, the city’s basement. Among antiquated voting cards, countless discarded mechanical parts, and a zoo of abandoned office furniture, I helped catalog a world of musical instruments.

The room, owned by the Schubert Club, was filled with the souvenirs of William Kugler, former Saint Paul bandleader. Sifting through the contents was like learning a new language. Gusles, erhus, balalaikas, and ouds. Each day, my colleague and I passed through metal detectors and disappeared into the deep end of Bill’s brain. We traded the heat of downtown Saint Paul for a world populated by a maniac musical magpie. Bill wasn’t discerning—as long as it made a noise, it was a music maker to him.

We wound through passages of concrete and gloom to reach the orange door that guarded the collection. The silence was over-whelming, yet the potential sound was palpable. Bill took his orchestra around the United States, bringing back anything that looked, sounded, or smelled like an instrument. He built an addition onto his house to hold his chimerical treasures. In 1989 the Schubert Club relieved Bill of decades of reveling in musical oddity. It was up to my colleague and me to reorganize his finds.

We started with the accordions. Shelf after shelf of glittering boxes with mother-of-pearl details and intricate inlay. Then an army’s worth of brass. It looked like the man had raided every high school in Minnesota for used instruments. I dared not think of the sanitary implications. Next came harmonicas, a Fort Knox of shiny bars in stacks.

After that we turned to the shelves full of what looked to be Indian instruments. Peacocks, crocodiles, and turtles stared back at us, holding feebly on to strings and frets. We tried to puzzle out the names of each instrument to create a faithful record of identity and provenance. One day we opened our Rosetta Stone—a box with the name and phone number of a Pakistani instrument manufacturer. It turned out that Bill had never been to any of the places the sitars and sarindas were made to look like they were from. He had a fervent desire, nonetheless, to experience the unknown. He liked to make friends with the unfamiliar.

As we unpacked and catalogued the spoils of Bill’s wanderings, we did our best to educate ourselves on the diverse instruments, but we could not know every object’s name and story. For every beloved and battered band instrument, there was a curious contraption we had no hope of identifying.

At times the silence was dispiriting—all this music unheard for years. Bill had led tours through his house, giving schoolchildren demonstrations of sounds they may never have otherwise heard. While his collection still had a home, it was now more somber than the original. But imagining the music that could be made from instruments we sometimes could not name gave our task the feel of a true adventure.

One day we discovered Bill’s mechanical music boxes. We opened the lids and marveled at the dazzling innards—beautiful rows of silver and gold, expertly engineered for sound. We wound one up, and the pieces came slowly back to life. We listened to songs that had not been heard in decades, if at all. I could almost feel the wood and skins of other instruments vibrating along to the melodies, embracing the lost sensation of sound. Somewhere, Bill Kugler heard the music. He had been listening all along.