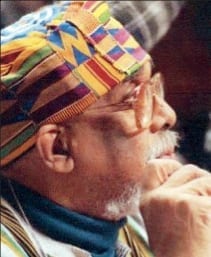

Photo Courtesy Mitchell Palmer McDonald

Mary K. Boyd—a well-known and much-loved educator—Kwame, and I made up a team that taught leadership training, cultural wellness, and life skills at Johnson High School on Saint Paul’s East Side. I joined the team in 2009. I will miss the mornings when he and I would ride together in his car to the school, listening to “Lean On Me,” which he always had playing on his stereo. He loved that song and was fond of the principal in the movie, Joe Clark. We would discuss what we were going to teach the students that day, and how we would encourage the young men in our class to be critical thinkers, to know who they are, and to love themselves.

Kwame was an avid sports fan who could be seen at many high school and college games. He was recognized and much loved by coaches and athletes across the state. At Johnson High School games, he always encouraged me to sit with him—most of the players were members of the class we taught. Kwame was easily recognized by students because of his regular attendance, and his symbolic African dress. You could see the admiration in the eyes of the students who would come up to him or wave at him. They all seemed to say, “We need you here in our school. You make us feel the importance of education.”

When he turned eighty we had a party at the school during classtime. He asked all of us, especially the students, “What do you think it will take to get to eighty years old?” Before anyone could answer, he talked about all he had done throughout his life, and most importantly, how he had never smoked or drank liquor. He didn’t talk about it like anyone else shouldn’t do it—just that he didn’t, and that those

were some of the choices that contributed to his long and productive life. I was a smoker and he knew it, but out of respect, I never smoked around him. Yet knowing how he felt about it, together with other positive influences in my life, I stopped cold turkey on the first of September 2011 and have not smoked since. I never told him that I had quit, and he never asked.

There are many, many things that I could write about in terms of my relationship with Kwame, but I can’t help remembering the time I directed him in a play called Somewhere Before in the late 70s or early 80s. One day during rehearsal he stopped in just to see what we were doing. He was so impressed with the play and the people in it that he said, “Man, I want to be a part of this.” Right then we started talking about it and wrote him into the script as a character called “BB Boldacious.” He was an instant hit in his role. We performed it in different places around the Twin Cities, including the Penumbra and Guthrie theaters.

Kwame was a man whose swagger complemented his tall and handsome figure, and he was a good dancer. It was during the three school years we worked together at Johnson High School that his illness became apparent. I began to notice how difficult it was becoming for him to walk, and the pain he was suffering, but he never complained; he would just say, “My legs ain’t working too good today.” Still, he

seldom used the walking stick that he brought home from Africa.

In early October 2011 I called Kwame to see when we would meet with the new principal at Johnson High School and talk about our next classes. He said to me, “Yes, we’d better do this soon because within two weeks or so, I will be leaving.”

“Leaving?” I said. “Where are you going?”

And he replied, “I’m about to die.”

I rushed over to the Golden Thyme coffee shop, where I knew he would be, and sure enough Kwame was in his regular chair by the door, talking to the people who usually gathered there when they knew he was in the house. They all had looks of disbelief and wonderment on their faces. I glanced over at Kwame, and there was this expression on his face that suggested his satisfaction at having informed the community of his demise.

After Kwame left the crowd looked at me and asked, “Elder Bobby, what should we do?” It was quickly determined that Kwame should “smell of his roses” while he was still alive. On October 7 we hosted a gathering at St. Paul Central High School. More than four hundred people came from all over Minnesota and beyond to show their appreciation and love to Kwame. There were proclamations from the governor’s office, county board, state legislature, city council, school district, and more. I arranged for SPNN to tape his last statement to the community. At the end of the celebration, right after his son Mitchell told some humorous and wonderful stories about life with his mother and father, the tape was played. Kwame admonished everyone to look out for one another, love themselves, and be watchful for opportunities to be of service. He spoke of his appreciation to everyone in the Saint Paul community for adopting him and his family and making them feel at home.

In late October 2011 Kwame was in the Sholom Hospice, where many people came to bid him farewell. So clearly was his courage, his fearlessness, his self-determination, and his understanding and acceptance of his fate revealed. It was rather tickling when people would tell him to eat so that he could get some nourishment, and he would look at them as if to say, “I’m dying, I don’t need nourishment!”

The last time I was with him he asked, “I wonder what’s taking so long?”

“What do you mean, ‘What’s taking so long?’” I asked.

“Death,” he replied. “Why are you taking so long? I am ready.” Kwame passed away early the next morning.

In conclusion I’m reminded of something my godfather used to tell me when I was very young. He always reminded me of what a gentleman is and should be. He would say, “Son, a gentleman is one who is gentle and refined in manner. He is courteous in deportment, magnificent in disposition, and temperate in habit. He doesn’t give in to strife or evil speaking, but maintains proper dignity and self-respect. He is mindful of the rights of others, and he’s truthful, honest, patient, benevolent, and humane.” He then would go on to say, “I like to meet a man who’s glad that he is Black, who is conscious of his color and realizes that fact. I like to meet a man who’s glad that he is White, for color makes no difference—any color’s all right. But I like to be with friends who distinctly understand that character makes a person, no color makes a man.”

In addition to all of the other good things about him, Kwame McDonald was a gentleman with much character. Farewell, beloved friend, teacher, and brother—you are missed. Hotep.