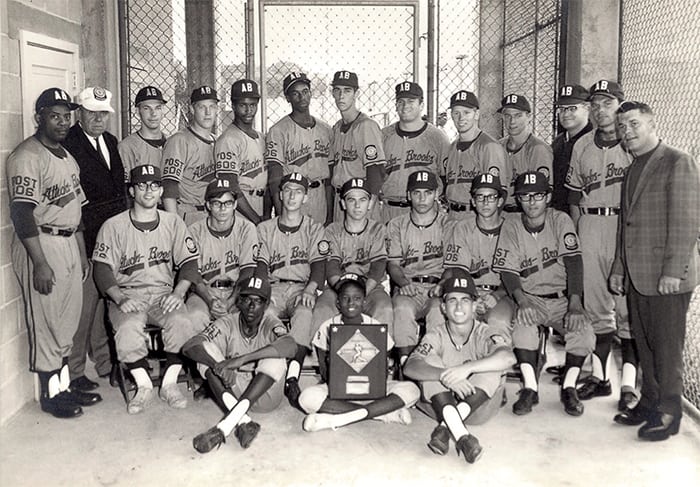

sixth from the left in the back row are Steve and Dave Winfield; standing at

far right is Coach Bill Peterson. Courtesy Bill Peterson

Billy Peterson has left his impression on Saint Paul baseball for

more than five decades. At seventy-three years old, he is a central

figure in the Midway Baseball program at the Dunning sports complex,

where one of the ball fields is named after him. I first met Billy

Peterson when I was eleven and attended one of his youth baseball

clinics. He was quite demanding as a coach.

During one clinic session as we did pre-workout stretches,

Coach Peterson shouted, “On the count of three, I’m going to clap

my hands. Then you’re all going to do a somersault.” That day, I realized:

I cannot do a somersault. I imagine that Billy Pete asked this

task of me because it is something that may be necessary when

making a difficult catch in the outfield. Needless to say, he was not

impressed with my acrobatics.

Since then, we have established a mutual respect that has led

him to refer to me as “That Smart Guy” and led me to sit down and

listen to him talk about his place in Saint Paul’s storied baseball

history.

SIDNEY CARLSON WHITE: Why are baseball and coaching so important

to you?

BILLY PETERSON: Baseball’s just part of my life. Like eating and

breathing. I have been playing baseball in Saint Paul since I was

ten. And I’m seventy-three. So that’s a long time. Except for the

three years I was in the Marine Corps, I’ve been a player, a coach, or

running the municipal athletics program, which I did for twentyfive

years. When I was fourteen, we moved from the East Side to

the Dale-Selby area. There was no organized baseball that I knew

of in that area, so my dad fundraised and we got a team in the city

league. I became a player-coach.

SCW: What was your first coaching job?

BP: I got my first coaching job at Oxford Community Center, believe

it or not, as a hockey coach in 1960 after I left the Marine Corps. I

had played baseball at the University of Minnesota, but I found out

there that as much as I had played and loved the game, I wasn’t

good enough to play at that level. So I started coaching baseball at

Oxford. At the U, I played under Dick Siebert and he had an assistant

named Glenn Gostick who was a fanatic about baseball fundamentals.

I learned from him that I didn’t know how to play the

game right. That’s what hooked me when I started coaching: Teach

the fundamentals.

SCW: So, I know that you have coached two Major League Baseball

Hall of Famers, and one who is almost sure to be there someday: Dave

Winfield, Paul Molitor, and Joe Mauer. Do you have any specific memories

from coaching them?

BP: I actually never coached Joe Mauer. He played in Midway for

one year, but he was too good so he played in a higher age bracket.

When I started coaching Winfield, he was ten, so that made me

about twenty. I didn’t have much experience judging kids’ playing

ability or a gauge as to how good Winfield really was. He was

better than all of the other kids, but since he was from Minnesota,

and I always heard about how rotten baseball is in Minnesota compared

to Florida, Texas, or California, it was hard to tell. When you

have kids at the starting point, when they’re ten years old, you sort

of grow with them. Like with your own kids. Dave and I grew up

together, he as a player, and I as a coach. His father wasn’t around,

so I was kind of like a surrogate father.

But memory-wise . . . We went to a state tournament together,

through American Legion, and were housed in a dormitory in St.

Cloud. Dave was a big joker. We were walking in the hallway and

these kids from another team walked by us and the coach started

talking. Dave, of course, jumps in, and asks, “Have you ever heard

of Dave Winfield?”

“No,” replied the coach.

“You will. Remember that name. You will.”

That’s the story a lot of people remember. A lot of my players

were there, and everyone was listening. That’s the kind of person

Dave is.

* * *

After he finishes answering, I quickly scribble something in my

notebook. Noticing I am writing left-handed, Coach Peterson asks,

“How long have you had this affliction?”

“What?” I ask, confused. Then he points at my left hand, the one

holding the pen.

“Being left-handed,” he adds.

“Oh. I’m not actually left-handed. I just happen to write lefthanded.”

Now at this point, most people would jump into an argument

that I am contradicting myself or that the hand you write with

dictates your handedness, but not Billy Pete. He simply replies,

“You’re kiddin’.”

“Nope,” I reply. “I bat right-handed, throw right-handed . . .” I

trail off.

“Wow.”

SCW: Do you have anything you want to share about coaching in

general?

BP: Well, I think I became a good coach after I coached my son. When

I first started coaching him, I had been coaching baseball for ten

years. I began to see the light when my older son left to play at a

higher level. One of my sons was a good athlete and the other was a good kid, so that son played too. But at higher levels, the younger

of the two got less playing time. I saw that when you coach, you

have to treat every kid like he’s your own kid. But you also have to

treat every kid like he’s not your own kid. You can’t play favorites.

At Oxford, I coached just about every sport, and what I learned, in

baseball, football, basketball, hockey, or softball, is that no matter

what game it is, kids come to play. They might not be very good, but

they come to play. This is especially important when their parents

come, not because a parent complains that their kid didn’t play, but

simply because the parents come to see their son or daughter play.

SCW: Why is having an inner-city baseball league so important?

BP: Well, I guess it’s just about as important as having any other

sport in the inner city, although there are not as many African

Americans playing baseball here at any level. Back in the day,

though, forty years ago, a lot of kids’ parents played baseball in

the summer, because there was nothing else to do. But today, most

of these young African American kids, their parents never played

baseball or softball.

Some people think baseball is a boring sport! Society today

moves fast, and baseball slows things down, and today’s youth

aren’t as attracted to the game as they once were. That’s why having

the inner-city league is important, so kids can be exposed to

baseball while they’re young. If kids decide at fourteen or fifteen

that they don’t want to play anymore, that’s okay, because at least

they got the opportunity to play.

* * *

Every summer more Billy Peterson stories get written on the field

that bears his name. Integral to the Midway Baseball program,

he is still coaching, and if you stop by the Dunning fields during

baseball season, you may see him mowing the grass. The Dunning

sports complex has many boosters, from parents of the boys and

girls who play there to baseball devotees who have been rounding

up donations at Hot Stove League banquets for years. The Friends

of Saint Paul Baseball continue to generate support, but no one is

more dedicated to youth baseball than Billy Peterson.